Letteratura anglo–americana 2013-14

| Letteratura anglo–americana 2013-14 |

|

|

JoHn Locke, Essay concerning Human Understanding

1. Our Knowledge conversant about our Ideas only.

Since the mind, in all its thoughts and reasonings, hath no other immediate object but its own ideas, which it alone does or can contemplate, it is evident that our knowledge is only conversant about them.

2. Knowledge is the Perception of the Agreement or Disagreement of two Ideas.

KNOWLEDGE then seems to me to be nothing but THE PERCEPTION OF THE

CONNEXION OF AND AGREEMENT, OR DISAGREEMENT AND REPUGNANCY OF ANY OF OUR IDEAS. In this alone it consists.Where this perception is, there is knowledge, and where it is not,

there, though we may fancy, guess, or believe, yet we always come short

of knowledge. For when we know that white is not black, what do we

else but perceive, that these two ideas do not agree? When we possess

ourselves with the utmost security of the demonstration, that the three

angles of a triangle are equal to two right ones, what do we more but

perceive, that equality to two right ones does necessarily agree to, and

is inseparable from, the three angles of a triangle?

...

3. This Agreement or Disagreement may be any of four sorts.

But to understand a little more distinctly wherein this agreement or

disagreement consists, I think we may reduce it all to these four sorts:I. IDENTITY, or DIVERSITY. II. RELATION. III. CO-EXISTENCE, or NECESSARY

CONNEXION. IV. REAL EXISTENCE.

,,,

1. Objection. 'Knowledge placed in our Ideas may be all unreal or

chimerical'I DOUBT not but my reader, by this time, may be apt to think that I have

been all this while only building a castle in the air; and be ready to

say to me:--'To what purpose all this stir? Knowledge, say you, is only the

perception of the agreement or disagreement of our own ideas: but who

knows what those ideas may be? Is there anything so extravagant as the

imaginations of men's brains? Where is the head that has no chimeras in

it? Or if there be a sober and a wise man, what difference will

there be, by your rules, between his knowledge and that of the most

extravagant fancy in the world? They both have their ideas, and perceive

their agreement and disagreement one with another. If there be any

difference between them, the advantage will be on the warm-headed man's

side, as having the more ideas, and the more lively. And so, by your

rules, he will be the MORE KNOWING. If it be true, that all knowledge

lies only in the perception of the agreement or disagreement of our own

ideas, the visions of an enthusiast and the reasonings of a sober man

will be equally certain. It is no matter how things are: so a man

observe but the agreement of his own imaginations, and talk conformably,

it is all truth, all certainty. Such castles in the air will be as

strongholds of truth, as the demonstrations of Euclid. That an harpy is

not a centaur is by this way as certain knowledge, and as much a truth,

as that a square is not a circle.'But of what use is all this fine knowledge of MEN'S OWN IMAGINATIONS,

to a man that inquires after the reality of things? It matters not what

men's fancies are, it is the knowledge of things that is only to be

prized: it is this alone gives a value to our reasonings, and preference

to one man's knowledge over another's, that it is of things as they

really are, and not of dreams and fancies.'

18. Recapitulation.Wherever we perceive the agreement or disagreement of any of our ideas,

there is certain knowledge: and wherever we are sure those ideas agree

with the reality of things, there is certain real knowledge. Of which

agreement of our ideas with the reality of things, having here given

the marks, I think, I have shown WHEREIN IT IS THAT CERTAINTY, REAL

CERTAINTY, CONSISTS. Which, whatever it was to others, was, I confess,

to me heretofore, one of those desiderata which I found great want of.

2. Instance: Whiteness of this Paper.

It is therefore the ACTUAL RECEIVING of ideas from without that gives

us notice of the existence of other things, and makes us know, that

something doth exist at that time without us, which causes that idea in

us; though perhaps we neither know nor consider how it does it. For it

takes not from the certainty of our senses, and the ideas we receive by

them, that we know not the manner wherein they are produced: v.g. whilst

I write this, I have, by the paper affecting my eyes, that idea produced

in my mind, which, whatever object causes, I call WHITE; by which I know

that that quality or accident (i.e. whose appearance before my eyes

always causes that idea) doth really exist, and hath a being without me.

And of this, the greatest assurance I can possibly have, and to which my

faculties can attain, is the testimony of my eyes, which are the proper

and sole judges of this thing; whose testimony I have reason to rely on

as so certain, that I can no more doubt, whilst I write this, that I

see white and black, and that something really exists that causes that

sensation in me, than that I write or move my hand; which is a certainty

as great as human nature is capable of, concerning the existence of

anything, but a man's self alone, and of God.

Pinson

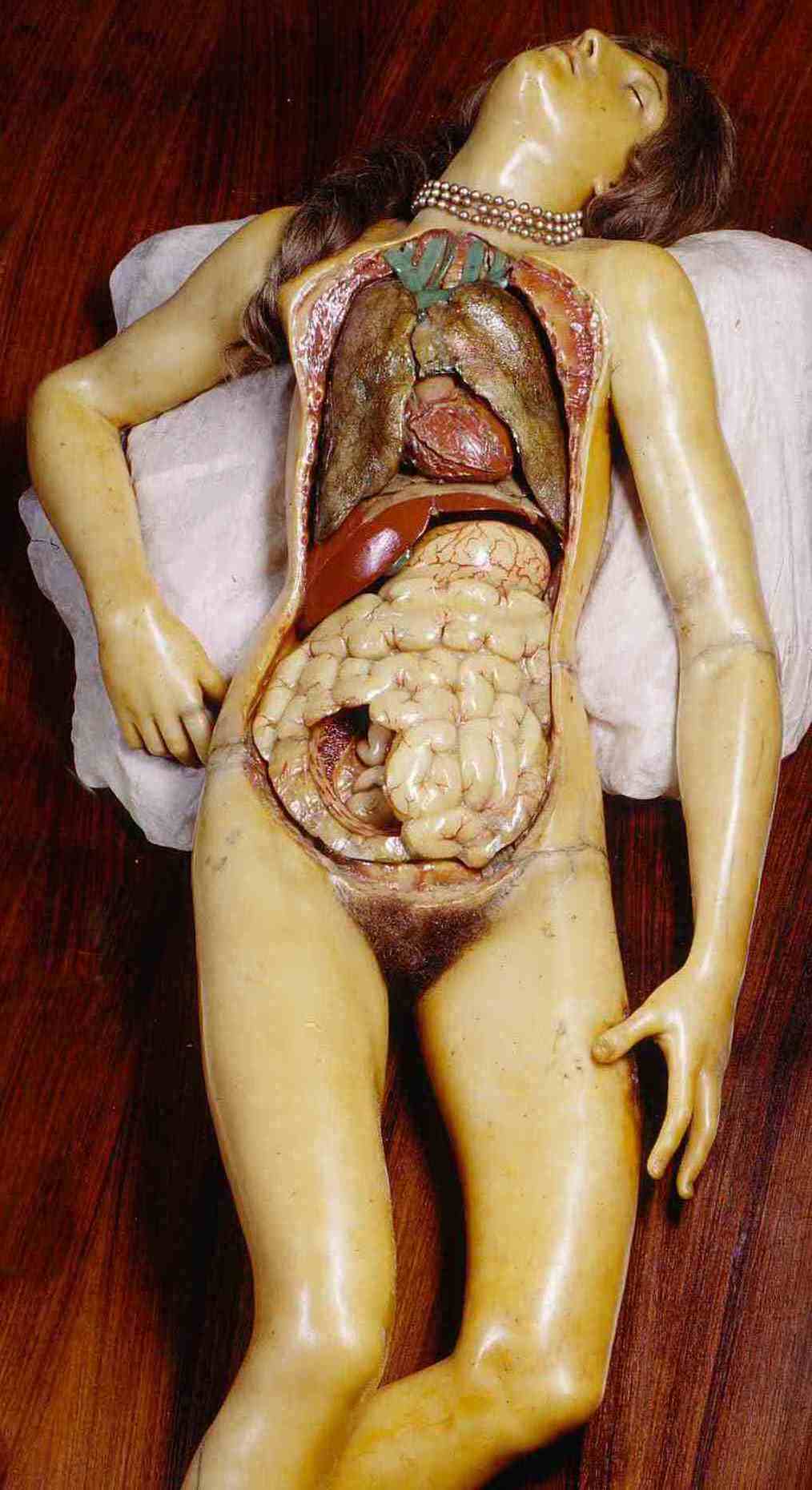

Clemente Susini (1757 – 1814), Venerina